Something Different:

We generally don’t do historical blogs on this site, though, I’m excited about my new book release, and it does focus quite a bit on San Francisco Bay. So join for a quick read on the history of the Spanish Maritime here in San Francisco Bay.

The book, “Ayala: The Coast of Spanish California,” was released at Barnes and Noble and Amazon on May 1, 2025. It is a comprehensive dive into the Spanish presence on the California Coast for three centuries.

What is there to know?

This is a big question. I frame the book in two competing lenses: 1st, the late 19th century and early 20th century publishers had it all wrong, purposefully. 2nd, the Spanish occupation of California was a disaster, and it only survived thanks to the amazing maritime feats that supplied the area year-after-year.

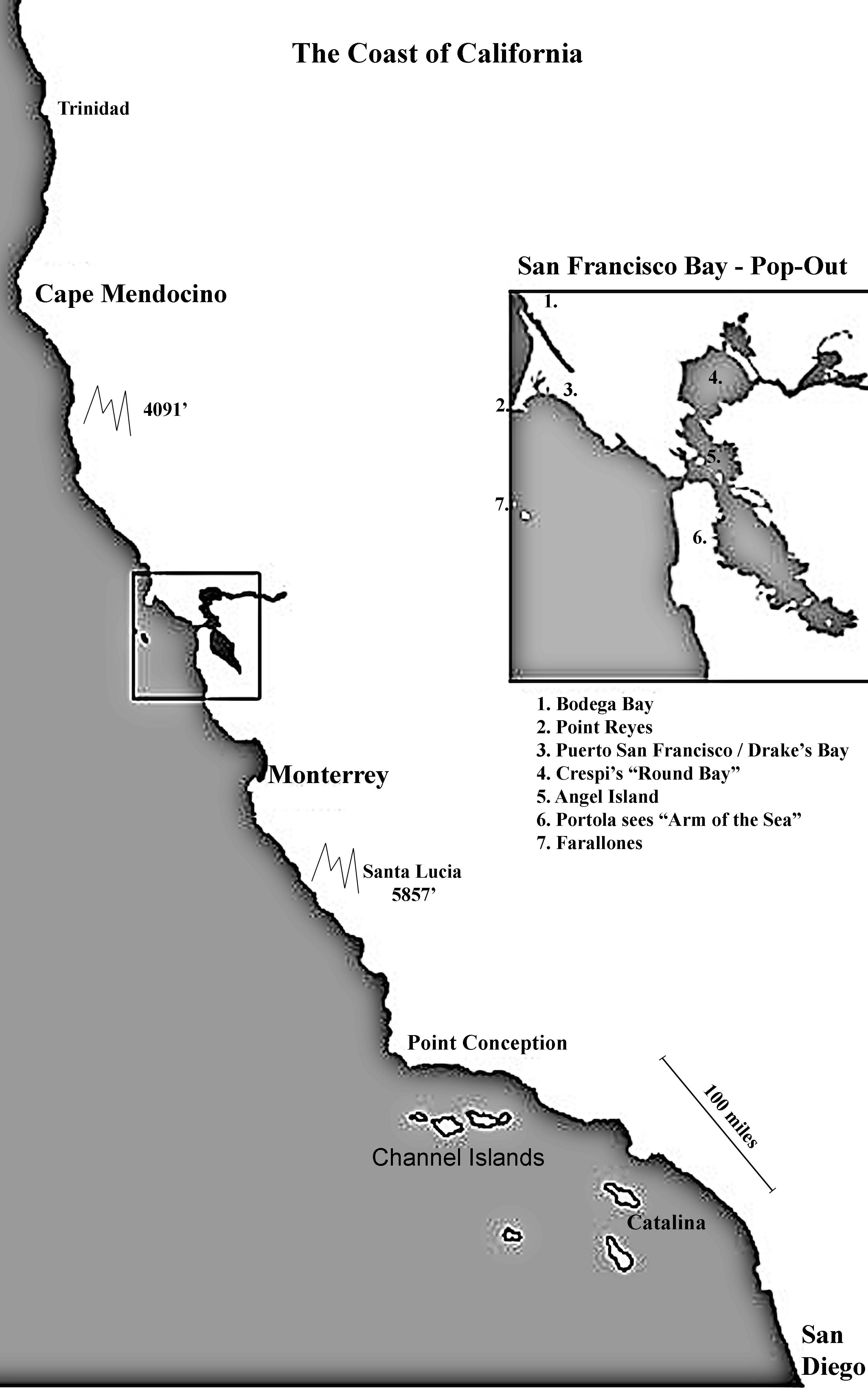

Many of you have heard about the failures of mariners to discover the Golden Gate, for centuries supposeduly, due to fog and a obfuscated shoreline. In the book I lay out a clear history of the vessels which were in the area to potentially discover the Golden Gate prior to Portola’s arrival in 1769, and there were only 6 expeditions which were close. Of those expeditions, each had good reason to stay clear of the area off of present day San Francisco, and fog wasn’t the largest factor. I argue that pseduo-claims like this, the fog-shrouded-entrance claim, interfere with our actual understanding of the Spanish on the California Coast – and even of the English and Russians on the Coast. Two centuries of misleading history has burdened the more fun conversation, of why the Galleons avoided the coast, why the northbound expeditions struggled to stay near the shore, and why the southbound fleets were warned to stay seaward of the Farralones.

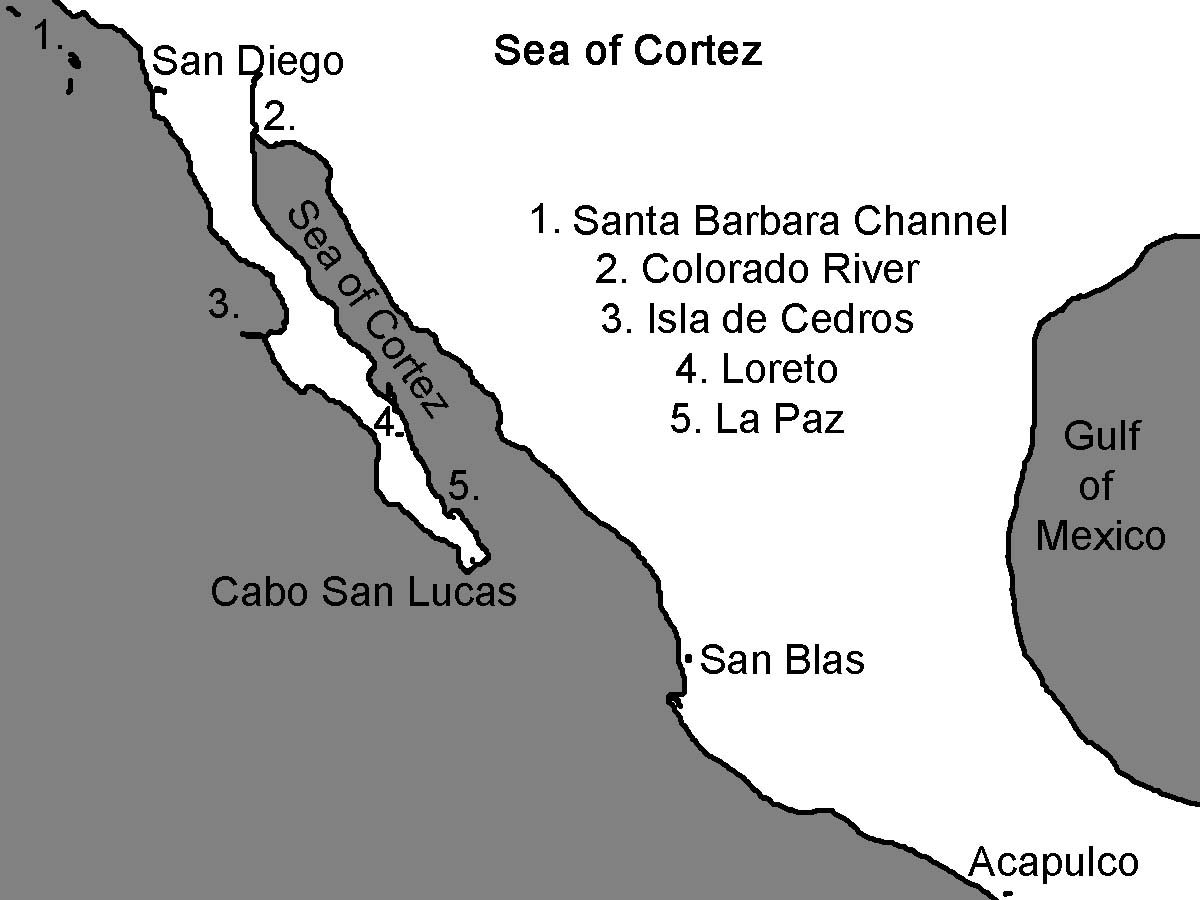

As for the survival of the Spanish outposts left by the Portola expedition, they were completely dependant on supply ships from San Blas Mexico. When the annual supply ships failed, which they sometimes did, waves of famine beat down the occupants of the Presidios and Missions. When 19th century publishers emphasized men like Junipero Serra and Gaspar Portola, they did so at the expense of others like Juan Perez, Vincent Vila, Bruno de Hezeta, and Juan de Ayala. The epertise of the mariners drove the little success the Spanish saw in Alta California.

What Mariners Were There?

There were three categories or maritime fleets on the Coast. The first were exploratory outfits; like the Cabrillo fleet, the Vizcaino fleet, and the Urdaneta voyage. These ships were ordered to scout the territory, chart shipping routes, and document their endeavor for future Spanish interests. Next came the Manila Galleons. These ships generally stayed away from the coast. Their only goal was to deliver their shipments of finished goods to Acapulco. While a few exceptions exist, they mainly avoided landfalls as they transited a clockwise loop around the Pacific Ocean. The exceptions were either ordered to search for safeharbors in Alta California (Gali in the 1580s, Unamuno in 1587, and Cermeño in 1595), or they missed their turns south (various detritus and animal spottings would signal approximate longitude) and wound up spotting the shore, normally south of Point Conception. Other than a few exploratory expeditions and galleons, and the Drake expedition needs to go in here, the only other ships on the coast came during and after the Portola Expedition in 1769. These were ships carrying supplies for the colonists, mainly food stores, building materials, military equipment, and religious paraphernalia.

While the book goes into detail on both the explorations and galleons, it’s truly the supply ships that garnish the most focus. This focus spawns from my preeminent character in the book, the Captain Juan de Ayala.

Who was Juan Manuel de Ayala y Aguirre?

Let’s review that name first, before answering the question. Bancroft gives him the name Juan Bautista de Ayala, which is wrong. And wikipedia gives him the name Juan Manuel de Ayala y Aranza, which is also wrong. I suspect wikipedia pulled the name from Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography, which is also wrong. An archivist wrote that same name, “Ayala y Aranza,” on Ayala’s military transcript at the Spanish Naval Archives – which I suspect is the origin of the mistake. The proper name, as said, is Juan Manuel de Ayala y Aguirre. Aguirre is Juan’s mother’s surname. Aranza is Juans Father’s mother’s surname. Therefore, Aguirre is the proper name, which is confirmed in Ayala’s signatures, specifically the signature he left on his Will and Testament in 1774.

But who was he? Other than the guy people say first sailed into San Francisco Bay? Well, we know that he was born into a upper class family in Osuna Spain. We know this because he was acceped into the Naval Academy when he was 16 – which suggest that his parents had ties to the Navy. Many Ayalas, Aguirres, and Aranzas were of the Noble class in Andalusia.

His first assignements at school mirrored the political landscape of the time. Ayala had entered just after the Seven Years’ War ended. This meant many ships of the fleet were at anchor and many officers were no longer needed. It was a poor prospect for a young cadet, and advancements would be hard earned.

Aboard his first few ships, Ayala studied under high ranking and prominent Naval Officers. He worked with two well known cartographers, including the men who mapped the agreed upon Treaty of Tordesillas line, dividing Brazil from Colonial Spanish territories, and the officer who had most recently charted the Straits of Magellan.

After graduating, and earning his official officer rank of Ship Ensign, Ayala would tranverse the Atlantic multiple times, and round Cape Horn three times, once while in a convoy carrying tons and tons of silver and gold from Peru.

Before recieving orders to San Blas New Spain, Ayala had encountered both Juan de Bodega and Bruno de Hezeta – two men who would accompany Ayala along the coast of California.

New Spain expands to Alta California

Portola and his men were sent north in 1768/69 because of a report from Russia that suggested a Russian fleet had landed on the Pacific Northwest Coast. This was true, but the reports were old. The Vitus Bering expedition from the 1740s landed in present day British Columbia, and had returned with reports of massive Sea Otters, which excited a small handful of investors in St. Petersburg. Portola marched north with a large herd of cattle, but he was completely dependent on the arrival of supply ships, to meet him in San Diego, and then in Monterrey (two ports Vizcaino had spoken highly of in his 1603 reports). Two ships arrived in San Diego, though the crews were mostly dead (90% died) and a third ship was lost at sea. The Portola expedition was a disaster, though it did leave two meagre outposts for Spain in Alta California. In 5 years those outposts would turn into 5 total outposts, including 5 missions and 2 presidios – all of which struggled to survive through constant bouts of famine and disease – they were at all times dependent on the supply ships from San Blas.

When a second report of Russian activity came, which was based on the same outdated information as the first, but this time spun up and amplified by a popular map that showed an English and Russian presence in the Pacific Northwest, the Spanish Council of Indies ordered New Spain’s Viceroy to take defensive action and to expel the foreigners and take possession of the lands up to 60° North. They also said they would send professional mariners (officers) to San Blas to help with the orders.

In comes Juan de Ayala.

As Ayala arrived, the expedition leader, Captain Bruno de Hezeta, had assigned him and two others to captain four separate ships – one of which had already departed to resupply San Diego. Ayala was to accompany Hezeta as the captain of the ship Sonora, which was built to survey shallow and coastal waters. But soon things shifted when another Captain, the person responsible for delivering goods to Monterrey and surveying San Francisco Bay, Captain Manrique, became frantic and showed signs of mental collapse. Ayala was given his command, and Juan de Bodega took Ayala’s spot.

Ayala departed Mexico on a vessel known to be a slug. Its cargo was improperly stowed. Its mast and sails were not functional. A week into the voyage Ayala shot himself in the foot on accident – he claimed that Manrique was responsible for having a loaded sidearm just lying around the cabin. The injury would ultimately take Ayala’s life, but the death would take a long painful decade.

He reached Monterrey 101 days later. Spent a month recovering in Monterrey, repairing his rotting ship, building a canoe, and devouring reports on the Golden Gate, created by the then Governor of California Rivera.

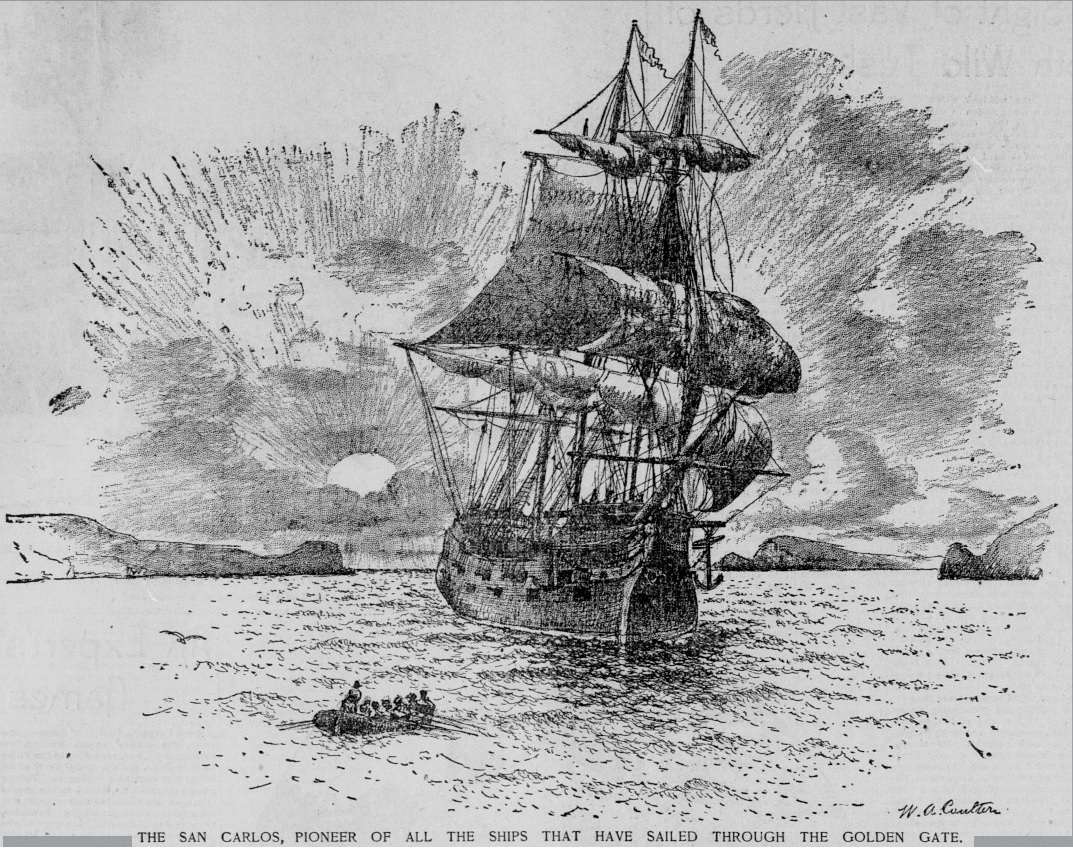

Ayala sailed for 5 days, 100 miles, from Monterrey before entering the Golden Gate. His First Pilot, Josef Canizares and 9 men (probably a mix of Filipinos, Baja Indians, African slaves, and Spanish and Portuguesse peasants) first took a launch into the Gate, to search for a safe anchorage.

In San Francsico Bay for over 40 days, Ayala remained on his vessel, nursing his wound. Canizares and the Second Pilot Aguirre sailed and rowed around the greater Bay, all the way past present day Antioch, taking soundings and collecting information to give to the approaching Anza Expedition (with 200 colonists).

The book goes into detail what happened from here, and clears up arguments on who created the 1775 survey map of San Francisco Bay.